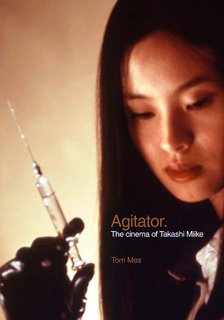

Agitator - The Cinema of Takashi Miike

If you like me were lucky enough to get swept up in the tide of contemporary Asian cinema that rocketed out from the smoky residue of the Ring of Fire a few years back, then the name of Takashi Miike will probably have some resonance in your mind. The seemingly sudden onslaught of fresh cinema raised it’s head just as time finished it’s creaking journey over the millennial horizon; about a half decade ago it was, back in the days when Christian Bale was only a psychopathic American, and not a factory-floor, proletariat Batman.

If you like me were lucky enough to get swept up in the tide of contemporary Asian cinema that rocketed out from the smoky residue of the Ring of Fire a few years back, then the name of Takashi Miike will probably have some resonance in your mind. The seemingly sudden onslaught of fresh cinema raised it’s head just as time finished it’s creaking journey over the millennial horizon; about a half decade ago it was, back in the days when Christian Bale was only a psychopathic American, and not a factory-floor, proletariat Batman.Although probably on the whole it’s more accurate to call it an industry renascence (it’s not like films ceased to be made), or an international renascence (since it’s about the awareness of English language audiences), nevertheless the unsoiled sheets became thoroughly soaked with spectres of ladies with long, dark hair, other ladies with long, dark hair, the occasional scary child bearing corpse-paint, and more ladies with long, dark hair.

In between the royal battles for the ring and murky waters and corridors, Miike showcased his oeuvre, directing a number of films to shock and surprise and do all that good stuff that gives publicists a litter of outrage to utilise in mad spasms of PR. The infamous torture of Audition, the masochism of Ichi the Killer, the whirlwind pace of Dead or Alive, all and more cemented a reputation for the little goggle-eyed man from

Agitator – The Cinema of Takashi Miike, as the name suggests, is a book all about Miike’s films, with various excursions into biographical territory. Authoring this exclusively on his lonesome, Tom Mes tackles every flick up to Deadly Outlaw: Rekka in 2002 (the book was published in 2003), dealing with each individually and working chronologically through a period of just over a decade. Segregating proceedings into chapters, he treats us to some preliminary words on Miike’s own background, as well as the prevailing thematic elements to recur in the exposition to follow; that exposition being the chapters three and four, which make up the great bulk of the book by acting as the canvas for Mes’s examination, one covering the early years in video, the other the post-1995 material.

From the outset little can be faulted here, comprehensive coverage of an entire filmography, along with specific details like cast and crew and DVD information suffixed as appendixes. His analyses evoke the proper level of depth, drawing from cultural and biographical context, as well as being sufficiently critical (this isn’t a fanboy writing an ode to his favourite filmmaker). He lambastes the director for his continued partnership with screenwriter and Manga artist Hisao Maki; one almost gets the image of a sweaty-browed Mes sitting in a darkened basement room, surrounded by wafts of transcript and draft chapters, frantically yelling at an abstract projection of Miike as he is forced into viewing another, as he would have it, “deplorable” and “dissonant” movie.

This is all fine as far as I’m concerned, attempts to hide the subjective are in general awry from the offset, and he backs up any opinions with a concise collective of reasons, judgements and comparisons. He dedicates more space to some films than others, understandably so as some just elicit more scope for discussion, via featuring more issues and so on. Notable here is that recent, more commercially and critically successful films garner more pages than their ancestors from the V-Cinema days, some of which have yet to even been given the English language title treatment. But these are not areas of contention.

Where Mes seems to fall down slightly is the at-times monotonous and repetitive nature of his discourse. Recurring themes are one thing, to continually return to the outcast protagonist and the psychological conflict of rootlessness is to underline things doubly where only a single line would be enough. His analysis has accuracy and he interacts with prevalent outside readings to a worthy extent, but it’s difficult to move away from the blockade that signposts a warning that ideas are being constantly recycled, with notions simply being conceptualised differently as the film in question warrants. And even then, often the rehash is barely distinguishable from the preceding method of communiqué; his writing frequently dips into banality, despite a perceivable endeavour to resist such, admittedly, easy pitfalls to fall into. His buzzwords are of particular annoyance, one cannot skirt over more than a few pages without coming across the likes of “apogee”, or “emphasise”, words that I can only assume are in high regard by him. Sure they’re decent words, although I’m not too hot on the former as I can only sound stupid saying it, but this regurgitation, this prosodic vomit, makes for unpleasant reading.

Perhaps this is where the crux comes rolling in: how to treat the book? As an encyclopaedia, a resource mixing factual and analytical, it works well. The extended synopsises are lacklustre as a piece of dinnertime reading, but viewed as purely referential, then the book functions on a better level.

Easily the best chapter is the sixth, which is a publication of Miike’s actual production diary from the creation process of Ichi the Killer. It’s a suitably unusual assemblage of snapshots from various points on the production, from the genesis (exhibited as a verbatim of Miike getting a phone call from the producer) to his arrival in America-land to promote the finished product. His stream of consciousness prose, eccentric and eclectic, is a joy to read, bounding in and out of dialogue, internal debate and philosophical digression. One moment he’s quantifying the amount of semen to have been expulsed in the city during the previous night, then he’s giving a rather dry bio of his screenwriter, then he’s off on some mad tangent about an dream allegory that seems to suggest CGI/digital filmmaking crushing the antiquity of bygone filmic techniques. His lack of linearity harks back to some of John Cage’s unrestrained writings, especially observable (visually as much as anything else) in a section where he goes into a double-spaced declaration about the creation process, a metaphysical mission statement about how the screenwriter adopts his project and “becomes Ichi the Killer.”

During the diary, Miike shows himself to be an intelligent and cerebral fellow, yet in the same instant retaining a down-to-earth realism, his self-deprecatory asides bringing amusement and an air of comfort. Directors tend to be mythologized according to their films, their output mirroring their own perceptions, and it goes without saying how erroneous this usually can be; certainly Miike seems far removed from the debauched, violent yakuza that regularly inhabit the space inside his camera lens. He’s as free from deluded ideals and prima donna posturing as you want from such a titan of Japanese cinema, like when he says, “the yakuza in my films are not real yakuza, they’re movie yakuza. Because the only yakuza I know are from watching movies.”

Let’s hope the honest and prolific (49 feature films in 11 years) director can continue executing his profession with as much panache and vigour as he has already shown. And let’s also hope that superior books, those not impaired by poor writing, can someday be summoned from the craters of Miike’s shaven skull and given a righteous place on a pedestal somewhere, maybe in Shinjuku itself.

1 Comments:

Excellent appraisal here, Sir Fleming. i've oft-times considered grabbing this tome, but i feel i may well wait for the inevitable revised edition. i've had something of a Miike craving of late, a craving that lay dormant for some time as you know, and was re-awakened by none but a chance re-watch of Ichi The Killer. I'd forgotten, to be perfectly honest, how sublime he can be.

Post a Comment

<< Home